Juan pablo Vizcaíno Cortijo

El que empuja no se cae (2020)

Dried coconut, paper, metal, light filters, epoxy, acrylic paint

22Hx24Wx6D (inches)

For purchase inquiries please contact the artist at juanpablovizcainoart@gmail.com

To learn more about the artist visit http://juanpablovizcainoart.com/

Juan Pablo Vizcaíno Cortijo

Recicle Vejigantes puppet at Villa Cañona.

Exhibition of Vejigantes masks

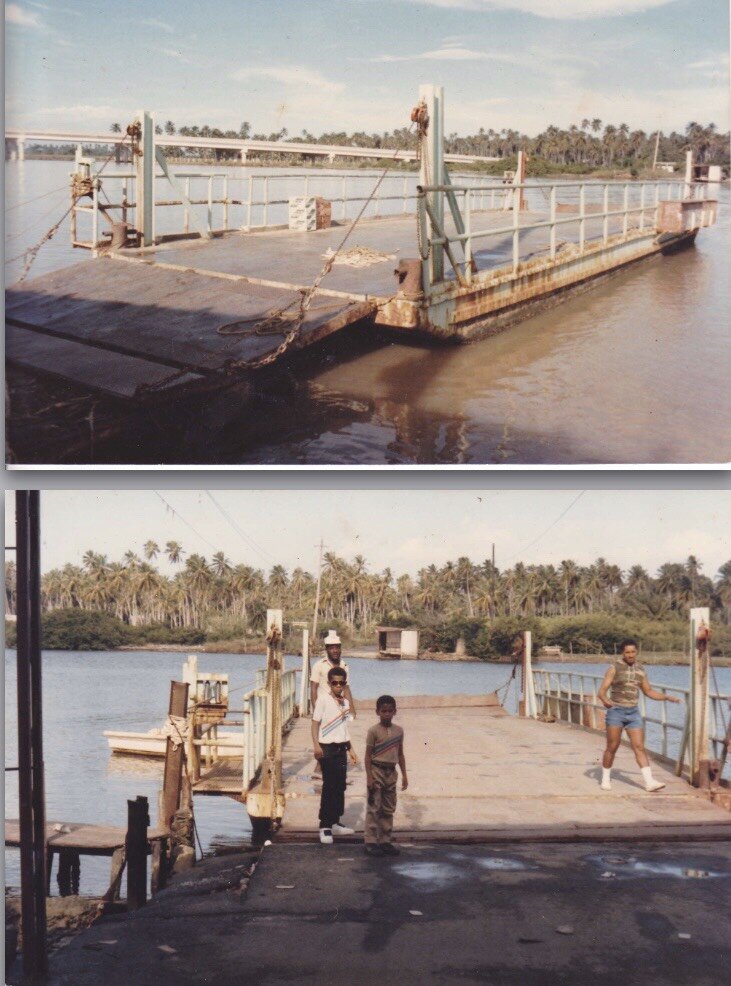

El Ancón de Loíza (River Barge)

El Ancón de Loíza (River Barge)

El Ancón de Loíza (River Barge)

Barber work by Vizcaíno Cortijo

Vizcaíno teaching a Children’s Workshop Making Masks

Children’s Workshop Making Masks

Vizcaíno building masks

Colaboración with artist Malcolm Ferrer

Vejigantes honoring Oscar Lòpez Rivera in NYC

Todes Vejigantes, a collaboration with Revista Etnica, 2019

Vizcaíno during the Todes Vejigantes Collaboration with Revista Etnica, 2019

Vejigante workshop and exhibition

Dey Hernandez at Comparsa de Villa.

Comparsa de Villa Cañona, “Cultura es Lucha” with Papel Machete. (The giant “El Prole” pictured in rear center wearing a red mask.)

Protest against development in Piñones

Vejigantes against development in Piñones.

Artist’s statement

Everything changed in 2020 as nature gave us an enormous shock. With COVID-19 killing many thousands, the community and solidarity we had achieved as a society disintegrated. During the pandemic, race riots and political protests drove us away from unity and towards tribalism.

Here we are, trying to survive in this new society that grows stranger every day. The community of the past is hard to remember as handshakes, hugs and kisses become rarer. We have become more paranoid and more detached from community life.

It is the year 2045 and I am protected by this mask that is itself a weapon. You can’t contaminate me. You can’t recognize me. And I can charge like an animal at any threat.

This mask carries the names of the ancestors of my tribe, my race, my people, who for centuries have suffered from injustice — Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Breonna Taylor, Ataliana Jefferson, Aura Rosser, Stephon Clark, Bothan Jean, Philando Castile, Freddie Gray, and hundreds more.

The mask, a reminder of what made us go tribal, is also what keeps us fighting for a more humane society, one based on equality and social justice.

About the Artist

Born in Santurce in 1978 and raised in Loíza, Puerto Rico, since childhood Juan Pablo Vizcaíno Cortijo has had an interest in the arts, music and traditions of his town. He grew up by the banks of a river, always inspired by its beauty and the beauty of the sea. He was also inspired by the rich culture that gave Loíza the name of Puerto Rico’s Capital of Tradition.

Juan saw the folkloric character of “el vejigante” — one of Loíza’s principal cultural symbols — as a defense of his hometown. He began carving vejigantes in 2006, following in the footsteps of master craftsmen like Castor Ayala, Raúl Ayala, Samuel Lind, and Juan Sánchez.

With his Vejigantes masks, Juan continues to contribute his art to his culture in hope of a better quality of life for all, while striving to keep his roots alive.

featured artist interview

From November 22 - 28, Juan Pablo Vizcaíno Cortijo was the featured artist for

The Babel Masks.

10 questions

1) You mention growing up on the banks of a river and near the sea. I know geography can affect our sense of aesthetic and influence the work we do later on. What sensory memories seem to always find their way into your work because of the landscape of living next to a riverside? What objects or materials have accompanied you in your work throughout your life?

Loíza’s landscape is unique in Puerto Rico. The banks of el Río Grande de Loíza, the estuary and the local and migratory birds, our wetlands, made me always feel that I was living in the village that Loíza is. Growing up in an era with minimal technology, Loíza gave us everything that we needed to play from sunrise to sunset – climbing trees, picking fruit, fishing and hunting. Just writing this, I can smell Loíza and my childhood in such a special place. The colors of Loíza kept me company in my art. Being in a coastal town, surrounded by mangroves and palm trees, beaches and rivers, it’s not difficult to be inspired. I work a lot with one of our symbols which is the Vejigante mask. This mask is made of coconut and is used during July in our traditional festivities.

2) You mention Loíza as Puerto Rico’s Capital of Tradition. Can you please share more about what that means to you and to the city as well as to Puerto Rico? What traditions is Loíza charged with keeping alive, and how does this status shape public life? What would you advise an artist visiting Loíza to be sure to visit to understand the city’s cultural life more thoroughly?

Loíza is known in Puerto Rico as the Capital of Traditions. It is an Afro-Caribbean town. The drums called tambores de bomba play all year long in Loíza. Our food is locally and internationally known: it’s a perfect mix of African and Taíno tradition. There is no other festival in the island like Santiago Apóstol.

Progress can be a terrible thing sometimes. It’s something that has always haunted us. And when progress gets together with political promises, it becomes even more dangerous. Loíza, like many black communities, has to deal with this challenge. It has become relatively simple for developers and politicians to present to the community the idea of “progress” with developments and housing that, according to them, will create jobs. Unfortunately some people will always fall for this, but some of us will always resist, and will present ways of progressing and growing as a community without putting ourselves at risk .

There are many examples, throughout the island, of gentrification and of the real estate developments going really badly for their residents. But like I said before, it is our art, music, food, and traditions that will keep us alive. Our ancestors are always watching our backs.

3) Who was your first teacher or mentor and what do you remember about the way he or she affected your life? What “artistic family” did you gather as you grew in your artistic practice?

Since 1920, my family was in charge of El Ancón de Loíza: a barge that carried people, animals, and cars from one side of El Río Grande de Loíza to the other. My house was right next to the port, so I grew up watching this cultural exchange, during the weekends, of people fascinated that they could put their cars on the barge and cross the river with a rope attached to a pole on each bank. It was such an attraction that Loíza artists painted images of the barge, my grandfather, the tourists arriving and other images of the area around my house. My family always bought their art to decorate our house and restaurant. I remember the pride of seeing el Ancón painted in Samuel and Daniel Lind’s art. That always inspired me.

Another thing was that every summer before our traditional festivities, local fishermen and people with their own skills would carve and paint their own masks to participate in our carnival. Others would buy them at Ayala’s Gift Shop, a family-run business which was the only mask-making workshop at the time and is now the oldest. All of these elements, and many more of Loíza’s traditions, continue to shape and inspire my art.

4) Can you please tell us more, in depth, about your work with Vejigante masks? What first drew you to these totems and when did you begin making them?

I opened my own barber shop in 1999. It was very successful. It stuck in my thoughts when so many people, after getting their hair cut, would call me an artist. It humbles me every time I hear this. I maintained a compromise between perfection and challenging myself. The culture of the barber shop, the history and community surrounding it, makes it something like a big family – there are always at least ten people gathered in that one single spot, talking about everything, and the story never ends, because hair always grows back.

The time came when I was long gone from Loíza , living and working in San Juan. But one time, after visiting old San Juan’s gallery nights, I came back home and felt an intense call from my roots to begin doing Vejigante masks.

There is no book about how to make Vejigantes. I had no computer and didn’t know much about the internet, so I started doing them on my own with what I could remember. I had a few problems with the paint and I still was working nights in the barber shop. So it was a bit challenging, and eventually I stopped doing masks.

Three years later, in 2006, I was watching the news. There was a story about a developer that wanted to build a hotel in my town: it was to be the biggest in the Caribbean. After work, my first stop was to the community center that was organizing meetings to protest and stop this project, and I offered my support. One of the many things we did in this campaign was to give Vejigante mask-making workshops for the kids of the community. I understood that planting those seeds during such a moment was very important: it was a therapy for those kids and their parents that were about to lose everything they knew of their own town to a monstrous development. The Vejigante became a healer, a protector, and once again a symbol of resistance of our people.

5) Can you share some more about your work with the radical puppet theater group – Papel Machete-Agitarte? What is its purpose and when was it founded? How has it unfolded as a cultural presence since its beginning? Did the Vejigantes lead you to the puppet theater or was it the other way around? What do you most wish this puppet theater group to build in the public consciousness?

It was during this fight against gentrification that I met Jorge Diaz and the group that he founded in Puerto Rico, called Papel Machete. He came to assist with an art play we were doing for the kids of the community. That play was going to be presented to the media, and right after we were going to have a press conference to talk about the status of our fight in court and the position of the community. After a successful afternoon involving the kids, local musicians, and the entire press of the country, I met again with Jorge at his art house, where I met more people from his group. I started to help prepare the puppets and construct full masks out of papier-mâché.

As I got to know the others in the group, I realized other communities throughout the island were going through situations similar to Loíza’s. I had always been environmentally and socially conscious since childhood, but this recognition was the defining moment that changed everything for me. I visited communities where, when it rained, the rain fell inside as much as it did outside. Even then the government and private entities were pushing them out without any consideration.

That was when my work as a barber, an artist, and an activist collided. I just couldn’t separate them anymore. It was a big mixture of thoughts that grew -- and continues growing, 14 years later on.

Using puppet interventions and shows, Papel Machete supported communities, teachers’ strikes, workers’ strikes, and national protests. Through puppetry I learned the power of masks, and the way that interaction and solidarity with workers develops. It is a process of making solid bridges from one community to another, helping each other fight to preserve what we knew as home.

I always treasure coming back to Loíza to take part in the carnival by bringing “El Prole” -- a puppet twelve feet high that is managed by three people. It required that I make a giant mask of wood and papier-mâché for “El Prole” and when put together the effect is really amazing. And I always look forward to seeing the kids of Loíza whose own masks came out of a workshop I did with them.

Papel Machete did another workshop in the community of Villa Cañona in Loíza that ended up being la Comparsa de Villa Cañona. Raúl, one of our group members, took the initiative to run a Vejigante mask-making workshop where they built the masks of reused materials and papier-mâché. The workshop also created a “la Mula Tuntunea” another of our traditional characters that hits the streets during Las Fiestas De Santiago Apostol.

At that time I was living in Virginia. For my part, I made nine coconut Vejigante masks to bring to the festival. I was under a lot of pressure to bring the best of me back to my community, as I was in pace with the work Papel Machete was doing in Villa Cañona. The reaction of Loíza as we came out was beautiful.

These traditions have been disappearing. Modernization and this absurdly fast world that we live in is shattering to pieces our essence as communities, as people. That’s why our interventions in Loíza aim to support the community in their struggle of maintaining their traditions and their own community life. Loíza is a precious place, and we can’t allow one more inch of our community to be sold to bigger interests who "quieren la jaula, no el pichon" (“they want the cage, but not the bird”). They want our beach, our nature, our history, but not us.

6) You mention that you are inspired by manifestations of Taino and African heritage. Can you please say more about the importance of these manifestations and that heritage, and what you have discovered as you bring these manifestations to audiences and exhibition spaces?

My town Loíza is named after the only Casica, "woman chief" of the Taínos, which were the natives of the island before we were colonized by the Spanish. Today Loíza is identified with and known for its Afro-Caribbean music, food, art, and culture in general. But if you look deeply into us, you will see Taíno manifestation everywhere.

Loíza is divided into various parts by rivers, mangroves, and lagoons. Taínos were known for their skill in piloting canoes and for being excellent fishermen, things that are true for our people in Loíza to this day. Some of our principal dishes in Loíza are also Taíno. As I I mentioned earlier, the majority of our community is black, but you can see the Taíno in us physically. Our music is Afro-Caribbean, our dances, our festivities and traditions.

How does that translate into my art? Well, when I make my Vejigantes, my heritage comes with them. Last year I did an art collaboration with the Afro-Latino magazine Revista Etnica. The magazine wanted to do a feature about a group of black people with different body types and different ways of love. Photographer Abey Charron photographed us wearing twelve of my Vejigante masks. My friend Jill and I did the makeup for each person to imitate the mask they were using. At first glance, the photographs seem to show a group of black people. But if you look at some of our faces, the Taíno comes straight out. We later transferred the photographs to bamboo planks and some planks from my aunt’s house, which had been destroyed by Hurricane Maria. We also used canvas made from the bamboo of the El Rio Grande de Loíza. The bamboo-based canvas was like a bamboo raft, and it was easy to imagine our Taíno ancestors navigating the river.

I have been fortunate in my collaborations with artists, galleries and spaces. People who come to my shows are intrigued by what they see. It's a little different when we do events, which always involve music and performance. They become an experience every time, like a super-cool history class, so audiences go home with an interesting story to tell.

7) How do you imagine your work may evolve in the next few years? What projects are you looking forward to? What books are you reading or what artists are you looking at right now?

My art today and my art tomorrow will go on fighting, just as my art today fights with my art from the past. I struggle between doing what I want to do and creating art that people would prefer to see. My art comes from a long tradition of carnival characters -- colorful, happy, festive. I notice that people want that, but I don't.

I keep reading political articles to know more about what's happening around the world. We now have so much access to information that news comes from all directions. As for books that inspire me, I look at books about African masks. Most of the investigations that led to these books agree on most things, but the various tribes of Africa have seen evolutions and mutations of their rituals and dances, so it’s difficult to know whether any of these books are still accurate or true.

8) In your artist’s statement you pronounce the names of Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Breonna Taylor, Ataliana Jefferson, Aura Rosser, Stephon Clark, Bothan Jean, Philando Castile, Freddie Gray as well as the names of ancestors of your tribe as being carried in your mask. How do you see the intersection between art and racial justice and social justice in your life? Can you share your perspective on the change you want to see and what change you do see happening? On a slightly different note, when artists make the Vejigante masks, is it part of the construction of a Vejigante to honor those who have gone by including their name in the creation of the mask?

When I put the names in my mask of these Afro-Americans and Latinos killed by police, I present them as the ancestors honored by this future tribe in the year 2120. In so doing I am describing the failure of government, but also the resistance and persistence of those who want to change our society. This future tribe continues surviving governmental and social disruption by staying together, arming themselves, and holding deep in their hearts their history and ancestors.

I posit that the future government failed because there is no justice for all. As for us, we have no other option except to continue. But we definitely need more balance in this society, more opportunities in our communities.

It is not part of our tradition in Loíza to put names in the masks. I just wanted to create a parallel world between black people in communities, future, present and past, always fighting to exist.

9) How would you explain the saying or proverb behind your mask’s title (“El que empuje no se cae” – he who pushes does not fall down)? What is the origin of this expression? How does it relate to this mask in particular?

There are many old sayings that I find myself repeating all the time. Getting older helps me appreciate them more. A simple proverb can sometimes be so sophisticated that it contains the question, the analysis, and the answer to your problem. They can also infuse a literal description with an incredibly deep metaphor. "El que empuja no se cae" is one of those.

It says, “the person that pushes, does not fall.” Most likely if you push someone, the other person will fall, not you. But in this context, the action is more like a redemption as the result of a straight action for justice. It’s like saying, “Let's move forward with our action as individual or as collective, because that is the only way out to gain our freedom.”

Here’s an example. A group of friends of mine, along with many other residents of the island, recently participated in a protest at the airport in Puerto Rico. In the COVID-19 pandemic, most Carribbean countries closed their airports, but Puerto Rico didn't. Rather, the airlines dropped their fares dramatically, and so an immense number of people from all over started to arrive in Puerto Rico. As a result, the number of COVID cases increased, people died, and hospitals were full. The demonstrators were demanding that the authorities gain control of the airport, and the situation got a bit tense when the police prevented the demonstration to reach the airport. That’s when my friend Victor revived that saying once again: "El que empuja no se cae.”

We must put the safety of our elders, our kids, and people above everything else. Unfortunately, our government doesn't control the airport, so demonstrations of conscience like this are very necessary.

The mask relates this protest as the moment when society crumbles, and you and your tribe will only survive if you fight together, honoring your ancestors and keeping their wisdom as your weapon.

10) What is the most exciting thing (or things) happening in your life right now?

I have my daughter Amelya, who is going to 6th grade next year, and my partner Anna who just gave birth five months ago to my son Khalid. And my family’s community center El Ancon de Loíza is almost done, and my art is breathing a different air today.